Buzzing: How well are edible insects doing?

Last week, I attended a webinar organised by Woven Network (the UK’s insect industry body) with Prof Arnold van Huis of the University of Wageningen in the Netherlands. Prof van Huis is widely regarded as the godfather of the insect as food and feed industry in the west. He was notably the lead author on the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) 2013 seminal report on insects as food and feed (it is the FAO’s most downloaded report in its history). So I was slightly taken aback to hear him say that insects as food were “not going that well”.

It’s true that edible insects remain a niche culinary interest in the west: according to the International Platform for Insects as Food and Feed (IPIFF), 9 million people ate insects in the EU in 2019, just 2% of the population. Recent consumer surveys from the EU and Australia also suggest that although consumers are open to the idea of changing their diets for environmental reasons, they have little appetite for insects (or lab-grown meat) and would rather opt for a vegetarian or vegan diet.

There are two ways of looking at this. On the one hand, you could argue that a 2% uptake is a pretty poor showing for a decade’s work. On the other hand, I am writing a newsletter about insects as food and feed. LOL. I don’t mean to suggest that my fortnightly musings will change the minds of millions (although I live in hope), but I would not be doing this if I didn’t think the growing interest in insects as food and feed signalled a fundamental shift in mindset about the impacts of our diets on the planet (amen).

A poll carried out last year by the Agricultural Biotechnology Council in the UK found that a third of Britons think insects will become mainstream by the end of the decade (see?!). More importantly, European insect producers have already raised more than €600 million worth of investment, a figure forecast to rise to €2.5 billion by the mid-2020s. Investors would not put this much skin in the game without being reasonably confident that they’ll get their money back (and some more). I keep thinking of that quote by Steve Jobs about how innovators must figure out what consumers are going to want before they do.

I think what van Huis and his fellow pioneers in the sector have done is plant a seed. Behavioural change is notoriously slow and as with every innovation, there will be a drip drip of early adopters before the majority floods in. Van Huis did acknowledge that all it would take for the whole thing to take off was a TV chef to suddenly take a fancy to crickets.

What do you think? I forgot to mention in the past that you can hit reply to this newsletter to email me your thoughts. Or hit me up on Twitter @EmilieFilou.

The Q&A: Dr Cortni Borgerson, Montclair State University

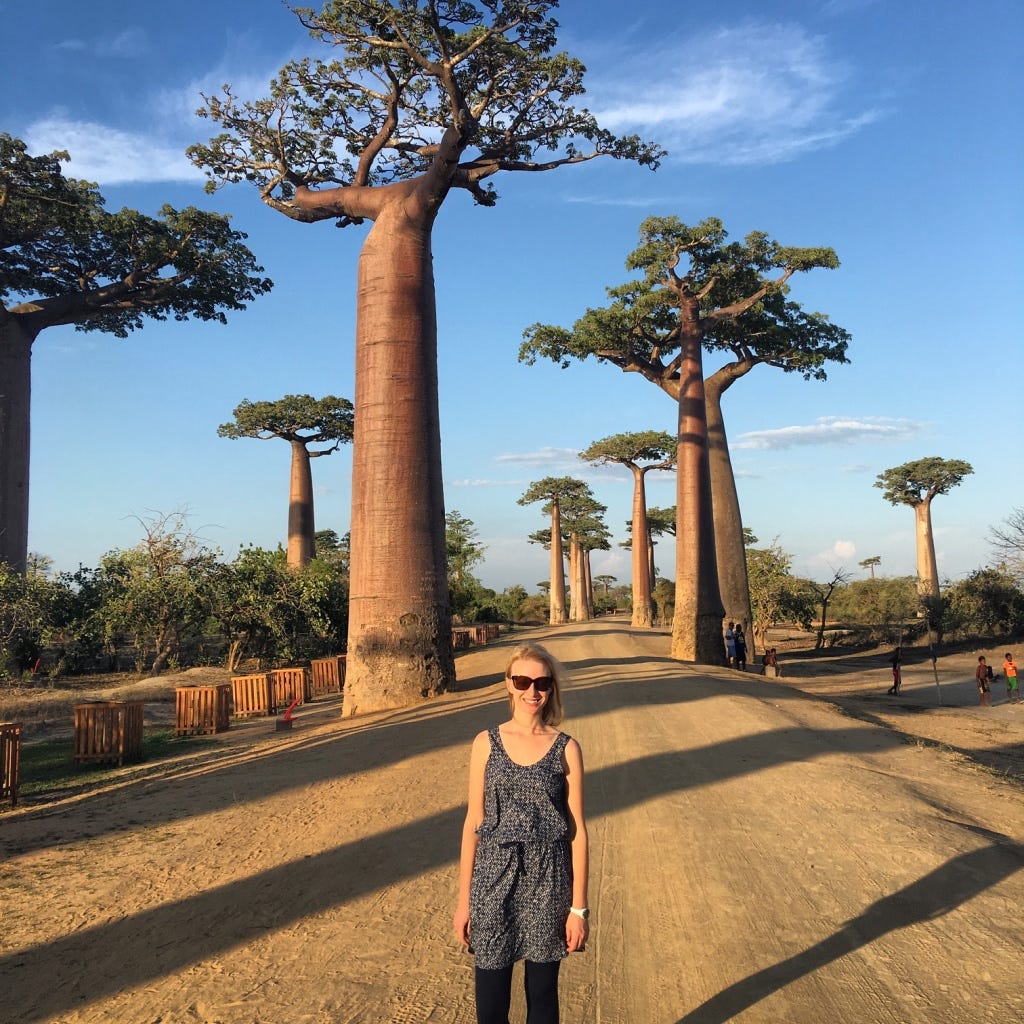

In May last year, ahead of a research trip, I was scouting for interesting lemur projects in Masoala in north-eastern Madagascar when someone suggested I speak to Cortni. I expected a pretty downbeat conversation on lemur hunting and traps; instead, I heard a formidable champion of local communities (she has lived in the northeast for fifteen years and speaks the local dialect fluently) talk passionately about her insect farming project. The premise was this: plant the host plant of a popular local insect called sakondry (Zanna tenebrosa) to increase its availability so that the insect, and surrounding forests, can provide a sustainable alternative to lemur meat. Cortni’s enthusiasm is infectious, which is probably why the project has been so successful. She is now looking to expand it across Madagascar.

How did a lemur conservation biologist end up farming insects?

If you want to reduce lemur hunting, you have to know why people are doing it. Traditional conservation can prevent access to the forest, which is very difficult for those who depend on the forest for their survival. People in rural Madagascar hunt endangered primates [lemurs], because of food insecurity: there isn't enough food, the lemurs are there, and they're easy to catch. We had to shift the incentives of the hunters. In the surveys we did of available and preferred alternatives to lemur meat, sakondry came up regularly as a favourite traditional meat, but it was only opportunistically harvested in small amounts. We just had to figure out a way to increase its availability.

What has your research shown to date?

Sakondry farming is a lot easier than lemur hunting. We found that the most active hunters halved their annual catch of lemurs and have become our most enthusiastic sakondry farmers. The communities we’ve worked with have harvested more than 90,000 sakondry in the first year of the project: this not only replaced but exceeded the nutritional value of hunted lemurs. Beyond that, no additional land was needed to achieve this success: we encouraged people to plant the host plant [a bean] close to their homes in under-used spaces such as along backyard fences and paths, and between existing crops to facilitate access. With our model, we know that any community, no matter how remote, can have a really established insect population within three months.

What do you make of current efforts to introduce mainstream insect consumption in the west: could it have unintended consequences on communities like those in Madagascar who rely on them for a high-quality source of protein?

The increasing demand for edible insects abroad is unlikely to affect the extremely remote communities we work with. Because our work aims to increase the availability of food, and not income, people eat the vast majority of the insects they farm. If sakondry continues to increase in popularity and demand (why wouldn't it? It tastes like bacon!), a foreign market could very well emerge. This is why we are currently working with our communities and private-sector partners to develop large-scale insect farming for urban areas. Overall, we’ve found that the growing interest in edible insects has had a positive impact: communities who traditionally eat insects can be stigmatised and the growing interest from people in towns and cities is changing that.

Test Corner: Eat Grub’s Crunchy Roasted Crickets

Eat Grub’s crickets were the first insects to be sold in a big supermarket in the UK (Sainsbury’s). I do remember hearing about it in late 2018 but this was before my Enlightenment, and I most definitely did not run to my nearest supermarket to buy some. They were, however, the first insects I tried in the UK post-Enlightenment, and my review from that first tasting could be summed up as “meh”.

I’ve tried many more insects since however, so I thought I’d give them another go. I brought a few packets to a picnic this summer and everyone tried them, which surprised me considering they are whole insects. They are small though, which perhaps helps (or it may just be that my friends are fearless gastronomes).

The crickets (£1.50 per packet) come in five familiar crisps flavours – smoky BBQ, peri-peri, sweet chilli and lime, salt & vinegar and salted toffee – in colourful packets. We tried the first three flavours and I’m sorry to say that my original review stands. I find the flavourings overwhelming and very salty. The spice in the sweet chilli and lime will blow your socks off too.

I understand the appeal of the snack format, especially as an “ice-breaker” for people new to insects. But it didn’t do it for me: I’ll stick to Eat Grub’s insect ingredients instead and look forward to trying more of their recipes.

Note: I do not accept freebies and buy all the products I try.

Hi, I’m Emilie Filou, a freelance journalist. I specialise in business and sustainability issues and have a long-standing interest in Africa. If you liked Buzzing, please share with friends and colleagues, or buy me a coffee. My funky cricket avatar was designed by Sheila Lukeni.